One does not read the correspondence of T.W. Adorno and Gershom Scholem on account of its authors, but because of its subject, their subject, Walter Benjamin. That three-way friendship is the ground bass of the correspondence: from Adorno’s first letter to Scholem in April, 1939, their shared concern is over the fate of this man who Adorno laments, following Benjamin’s suicide at the French-Spanish border little more than a year later, as “the only guarantor of hope”; then the effort to understand and come to terms with a death that both consider, again in Adorno’s words, “so dreadful and senseless that any consolation and any explanation are equally in vain”; and finally, for decades, their shared, heroic effort to keep Benjamin’s name alive, to gather his scattered writings, to see them through to publication, and to defend and—as they saw fit—define his reputation. Having grown used to thinking of Benjamin as cannily triangulating among three profoundly influential but profoundly conflicting friendships (the third one being, of course, with Bertolt Brecht) I found it eye-opening to notice, through these letters, the real (and ever-growing) warmth between Adorno and Scholem, men whose ideas were so different. While it’s clear from the beginning that Adorno (who at one point describes his intention “to reach materialism, in a very specific sense, not to set out from it”) is fascinated by the theological content of Scholem’s work. Scholem, at first, is rather circumspect about the books Adorno keeps sending him, pleading his unfamiliarity with the areas of Adorno’s interest. He spares Adorno his true response to the chapter on anti-Semitism in his and Max Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment: “Awful in its Marxist mendacity!” Luckily for Scholem and Adorno, avowed anti-Marxist and heterodox Western Marxist respectively, they can share their regret at Brecht’s influence on Benjamin. Adorno wrote to a third party that

while Benjamin was committed to Marxism, he hadn’t understood the essential content of Marx’s theory.” As for Brecht, “his ignorance of Marxism—down to the best-known things, such as the theory of surplus value—was quite indescribable. Neither of them had studied Marx’s works in earnest. Rather, to adapt what Hobbes once said about religion, they had swallowed it like a pill. In contrast to the materialist dialectic as a theory, their Marxism seemed heteronymous and irrational to me.

What seems faint in Adorno’s Marxism is class struggle, though at one point—replying to a long letter (dated 1 March 1967) in which Scholem, despite his professed indifference to Marxism, offers some shrewd, even profound critical observations on Adorno’s version of it—Adorno allows that it “remains indispensable for the construction of history and, with it, philosophy.” Yet it’s impossible not to notice the dearth of reference to real historical events on Adorno’s part, aside from an infamous assurance to Scholem that “I am one of a very few people who consider the actions of Israel, France, and England”—in initiating the Suez War of 1956—“to be right and fortunate.” In any case, it might be that, despite their weakness in theory, Brecht and even Benjamin had a surer sense of what class struggle meant (as Benjamin said, “a fight for the crude and material things without which no refined and spiritual things could exist”) than Adorno. Even more vehement than Scholem and Adorno’s shared suspicion of Brecht was the two men’s disdain for Hannah Arendt, their true bête noir, a subject in itself that I won’t go into here, though in Scholem’s case this evidently had to do with her critical position on Israel, which in retrospect turns out to have been far more foresighted than his. Here I have to mention something barely alluded to in the letters, but which their editor, Asaf Angermann discusses in detail: The fate of Paul Klee’s Angelus novus, which had belonged to Benjamin. I can’t say it ever struck me to wonder exactly how it came into Scholem’s possession, and thus after his death into the collection of the Israel Museum. As Angermann explains, Benjamin had in 1932, contemplating suicide, drawn up a will in which the painting was left to Scholem, but the will was later considered void and after Benjamin’s death, the painting became the property of his son Stefan. On leaving Paris in 1940, Benjamin had concealed the work among the papers he’d put in a suitcase and given Georges Bataille for safekeeping in the Bibliothèque nationale where he worked. The suitcase was sent to Adorno in California after the war, and Stefan Benjamin offered to allow him to keep the painting during his lifetime. But after Adorno’s death, Scholem asserted ownership. In a way that still remains mysterious after reading Angermann’s account, the publisher Siegfried Unseld, following Stefan Benjamin’s death, prevailed on his widow (in a manner “she reportedly still considered unjust in the following years”) to give it up. Scholem then smuggled it into Israel in order to avoid paying customs duty. As Angermann observes,

It is perhaps emblematic to the triangular and tri-continental relationship of Adorno, Benjamin, and Scholem that the long story of the Angelus novus, designated as the angel of history, began in Germany, continued in America, and ended up—through power plays, instrumental interests, and possibly some possessive trickery—in Jerusalem

—where, as Benjamin might have added, it has a closer view of the catastrophe of history than it might have had anywhere else.

❂

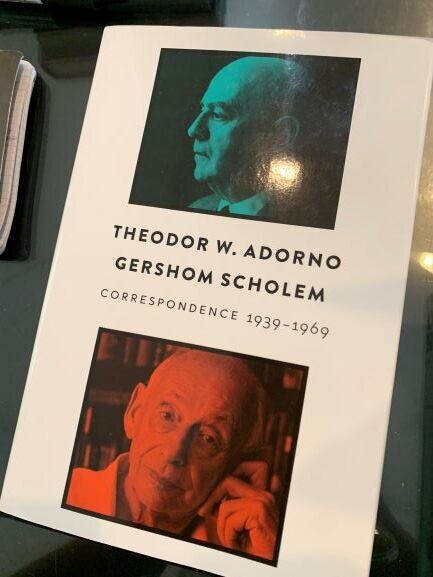

Theodor W. Adorno and Gershom Scholem, Correspondence 1939-1969, edited and with an introduction by Asaf Angermann, translated by Paula Schwebel and Sebastian Truskolaski, Polity Press, Cambridge, UK, 2021.

❂

BARRY SCHWABSKY is art critic for The Nation and co-editor of international reviews for Artforum. Along with many books on contemporary art, he’s published three books and several chapbooks of poetry as well as a collection of mainly literary criticism, Heretics of Language (Black Square Editions, 2017). His new book of poetry, A Feeling of And, will be published next year by Black Square.