Writing in 1983, Lorraine O’Grady declared, “I have a problem with the name ‘performance,’” going on to explain, “If pressed to describe what I do, I say I am writing in space.” That means—sorry to display once again my obsession here—that although she takes Charles Baudelaire as her leading light among poets, the form of her work derives, instead, from Stéphane Mallarmé, who first established spatial writing as a frontier for modernism. And if O’Grady is not exactly a performance artist, she might not be quite a performance artist either. This selection from nearly five decades of writing is a reminder that, more than an innately visual thinker, she is a literary intellectual who happened to find the proper medium for her writing activity in the new art forms that emerged in the 1960s under the guise of conceptual art. O’Grady’s back story is a long one. And if there is not already a biographer beating the bushes for the full story of this life, there’s something wrong out there. She was born in Boston in 1934 to parents originally from Jamaica, and was, she’s said, subjected to “an exceptionally traditional and elitist education, which I had to work hard to rid myself of in order to become an artist”—Girls’ Latin School, which Wikipedia informs me was “the first college preparatory high school for girls in the United States,” followed by Wellesley and then, after an unhappy stint working for the government, the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. She translated her Iowa prof José Donoso’s novel This Sunday, ran a translation agency in Chicago, and in New York took up music criticism for the Village Voice and Rolling Stone. Now in her forties, she picked up some teaching at the School of Visual Arts—notably, a course on Futurist, Dada, and Surrealist writing (Tristan Tzara is a favorite)—and this, it seems, prompted her to want to find out more about the so-called visual arts. A visit to the Wilentz brothers’ late lamented 8th Street Bookshop (†1979) turned up gold:

Lucy Lippard’s Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object. It was the first art book I ever read, and it totally changed my life…. By the time I finished that history of the conceptual art movement and all its subgenres—performance art, body art, earth art, and so on—I said to myself, “I can do that, and what’s more, I know I can do it better than most of the people who are doing it.” You see, I was always having those ideas, but I didn’t know what to do with them. I didn’t know they could be art, and until then, I hadn’t been in a position, in an intellectual milieu to discover it.

So much depends on the permission granted by circumstance. But O’Grady’s ideas remain as good for poetry as for art. Her first works might just as easily have been called poetry, in fact—cut-ups from New York Times headlines that look like haiku from a B-movie kidnapper. For me—maybe because back in the day I wrote enough for that paper to develop an allergy—they retain too much of the headline writer’s arch tone to be entirely satisfying, but her concept of learning “about the culture and about myself” by working on an external source in order to craft what she calls “a ‘counter-confessional’ poetry that made the public private again” sums up what still seems to be one of the great tasks of poetry, a way of working that I recognize in myself and in so many of the poets I admire. This counter-confessional mode of writing in space develops differently in O’Grady’s subsequent work, such as her great, high-spirited Art Is… project, which began as an event in 1983 and took its definitive form as a group of photographs in 2009, and you can see why she eventually had to learn to live with the designation of performance artist. And she never stopped being a critic. But, my fellow poets, she remains secretly one of us.

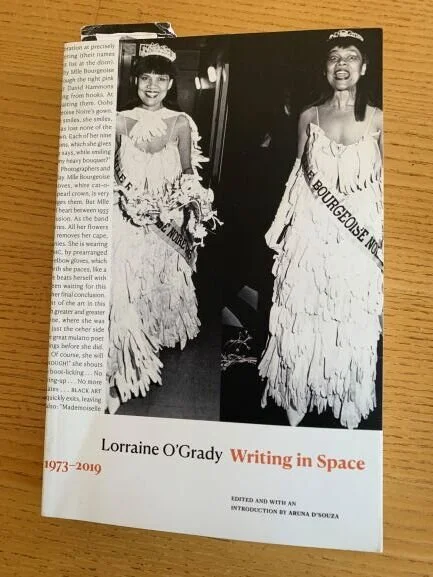

Lorraine O’Grady, Writing in Space, 1973-2019, edited and with an Introduction by Aruna D’Souza, is published by Duke University Press, Durham, 2020.

❂

BARRY SCHWABSKY is art critic for The Nation and co-editor of international reviews for Artforum. Along with many books on contemporary art, he’s published three books and several chapbooks of poetry as well as a collection of mainly literary criticism, Heretics of Language (Black Square Editions, 2017). His new book of poetry, A Feeling of And, will be published next year by Black Square.